Every Book is a Database

Last week I asked Marcin somewhere around the two hour mark of the Shift Happens livestream to show us his database; it’s perhaps the second most impressive artifact he’s made after the book itself (which just crossed the $500,000 mark over on Kickstarter with more than 3000 backers). Marcin has poured countless hours into this database archiving images and notes, compiling an enormous hive-mind of keyboard-related ephemera.

Over the years this database has become an artificial co-collaborator so that Marcin can easily cross-reference and draw connections between unlikely things. It’s sort of like having your own personal search engine, a tailor-made wiki built just for you.

It’s exciting stuff, listening to Marcin describe his book. He sees this printed thing as a kind of programmable interface like any other software project, but he’s also onto something even more exciting in this chat that I’ve never seen before, a lesson deep down that’s hard to put words to.

But here, let me take a crack at it; every book is a database.

That might sound rather cynical, as if all books are nothing more than columns rendered from a heartless data center a thousand miles away. But treating a book like a database means that you can collect research and quotes and everything all in one place and let the book grow slowly over time. As the database expands, the connections between subjects and ideas multiply, with the difficulty of writing the damn book slowly fading with it.

To put it bluntly: treating a book like a database helps you play with the subject of the book without all the pressure of having to write a book. Marcin didn’t say this in our chat, but I reckon that writing a book like this eventually becomes a matter of transcribing this hefty database back into words. Tough, for sure. But now you’ve got endless things to write about.

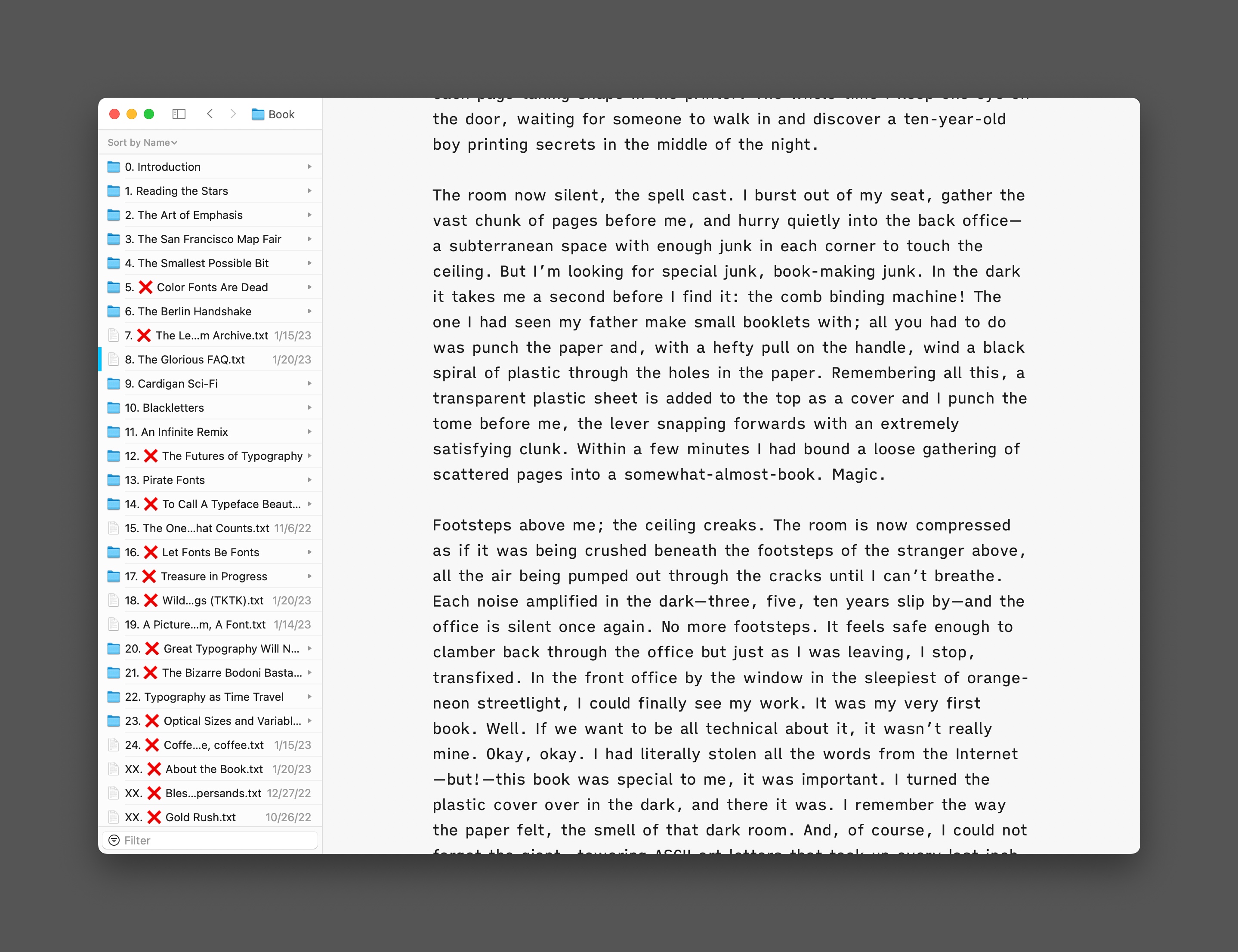

That sounds simple, and it’s not, but it’s much easier than the way I’ve been treating my own book-writing-process. Up until now I’ve been writing Letters as if it’s a script for a movie or an outline for a novel and my hunch is that’s precisely why the writing has been so slow. Instead, I need to build a database of reference material and collect vast troves of information — typefaces and books and quotes and images and spreadsheets. I need typographic data!

iA Writer is no longer the right tool for this job then because it’s best designed for little snippets of text and blog posts and not making databases.

Pictured above: my “process.” Welp.

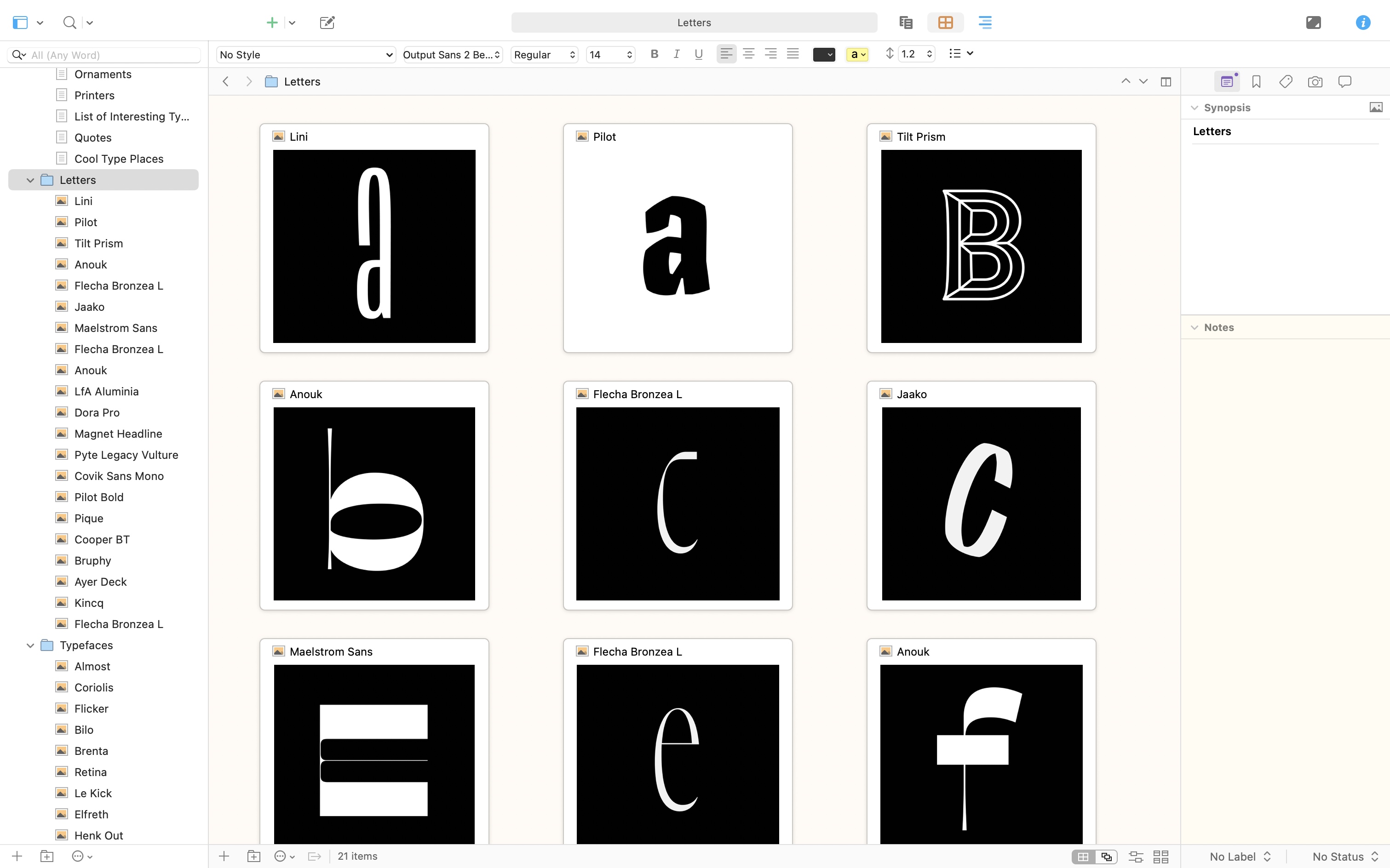

So this weekend I moved everything over to Scrivener and, after a few hours of fun, listening to quiet goth music in the background, I knew this was the right step. Five, six hours passed by in a flash as I now had this electronic buddy that I could riff with and just make endless lists and notes and ideas in any order that I liked.

Here’s how Scrivener is described in the tutorial doc they provide you with:

Scrivener projects aren’t only for storing text. Much writing requires research, and you can import your research documents—images, PDF files, web pages, even movie and sound files—directly into Scrivener. You can then refer to your research right alongside your writing.

At first I thought, huh, what’s the difference between this and Word? But no, Scrivener is the perfect tool for database-making. One example being a list of beautiful letters I made that I can quickly skim through at a moment’s notice:

Give it a few months and this little archive will be filled with hundreds of examples of beautiful typefaces that I want to cover or pick out in the book. But perhaps the greatest advantage I see already is that I can now quickly search across all my notes and images.

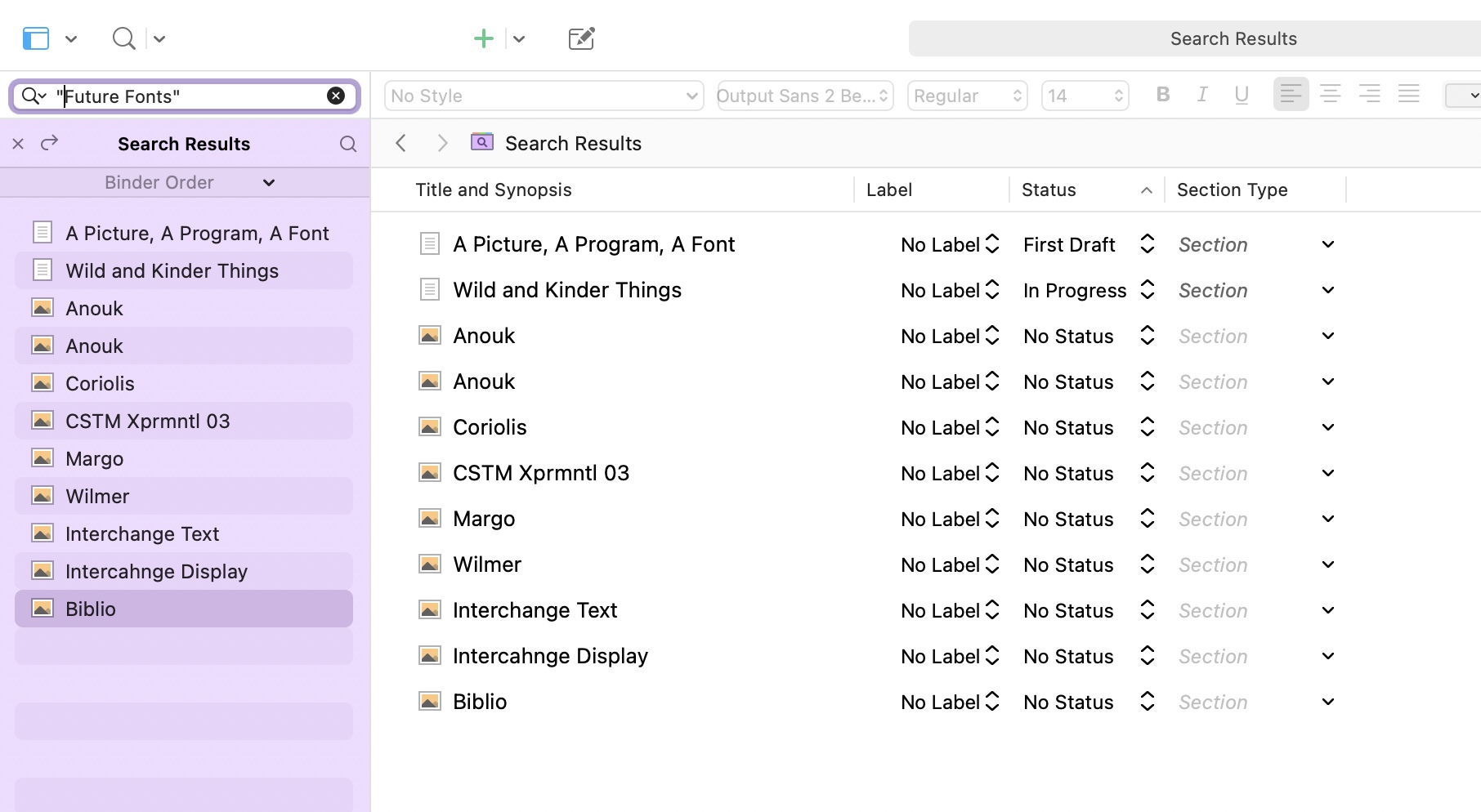

Like in the example below, where I’ve searched for “Future Fonts”:

This is amazing! I can see two chapters of the book where I’ve mentioned the name, plus half a dozen fonts that originated on the Future Fonts website. This is remarkably helpful, and as this book grows in scale and complexity it’ll be a handy tool for making sure I don’t keep writing in circles and copying older things I’ve written.

It’s only been a few days and this database is already drawing connections in my work, hyper-linking ideas together.

So! Although not much actual writing was done—only a thousand words or so—I do believe a substantial something clicked this week for the book. I can already tell that this is the tool and process I’ve needed since the beginning, but more importantly that this is now the right way to approach this book; Letters is a database in longform.

Now let’s go build that database.